Editor’s note: It’s the season for reflection, and we turned to design critic Julie Lasky for an atypical look at retail design in a reverse-engineered study on aesthetic inspiration. She pairs a few well-known retail brands with well-known art masterpieces and observations on what’s hidden in plain sight. Enjoy this holiday look into retail and art appreciation.

By way of prelude, several masterpieces could have served as mood boards for modern retailers. Great artists earn their reputations because of their power to capture a moment, an experience, or a style. Even when such works don’t actively contribute to the look of today’s world, they are shared references that can’t help shaping the way contemporary interiors are designed and seen. Here are a few examples, all spotted in New York City.

LoveShack Fancy and Jean-Honoré Fragonard

Step into the pink and floral world of any LoveShackFancy boutique, and what do you see? Girly-girl dresses and garlands of roses, and maybe, in your mind’s eye, the image of a young woman on a swing? You would be excused if the ultra-feminine fashion retailer sparked a recollection of The Swing, a famously romantic painting by the 18th-century French artist Jean-Honoré Fragonard. The central figure in that classic work is wrapped in a billowing, lace-trimmed, rose-colored gown as she floats dreamily through the air in a private grove. A carpet of blossoms lies at her feet. So does an adoring young man. Has anyone ever improved on Fragonard’s interpretation of “Love” and “Fancy” (though admittedly, “Shack” suggests a different vibe)? Both the Rococo painting and the modern store are nooks of indulgence, places where one is always young and the season is always springtime.

SKIMS and Giorgio de Chirico

Rafael de Cardenas may not have been thinking of Giorgio de Chirico’s 1927 painting The Shores of Thessaly when he designed the SKIMS flagship boutique on Fifth Avenue, but come on. In both shop and canvas, architecture is treated like anatomy and anatomy like architecture, with sensuous forms and a chalky palette.

C.O. Bigelow and Norman Rockwell

The oldest continuously operating pharmacy in New York, C.O. Bigelow, on Sixth Avenue in Greenwich Village, is a wood-wrapped time capsule that was founded in 1838 as the Village Apothecary Shoppe. “Legend has it that Thomas Edison soothed his burnt fingers with Bigelow’s balm whilst testing an early prototype of his light bulb,” the website recounts. It was 88 years later that Norman Rockwell illustrated a similar interior in his 1926 advertisement for Dixon Ticonderoga pencils, but both environments are emissaries from the same land of Mom-and-Pop nostalgia.

Printemps and Antoni Gaudí

Last March, Printemps, the Parisian luxury emporium, opened on One Wall Street, in a 1930s building that formerly housed the Bank of New York. “It is not a department store,” insisted Laura Gonzalez, who designed Printemps’s 10 highly differentiated and highly decorated spaces. The exuberance, the audacity, the sculptural curves — as in the building’s restored Art Deco Red Room, now a shoe salon — evoke the delirious originality of the Spanish architect and designer Antoni Gaudí (1852-1926). While Gaudí just preceded Art Deco, he shared the movement’s emphasis on nature, craft, and ornamentation.

Bloomingdale’s and William Girometti

The main floor of Bloomingdale’s New York locations offers a dazzling experience for shoppers intoxicated by jewelry, cosmetics, and checkerboard floors. In fact, you could say it’s downright surrealist, especially if you compare it with Portrait of an Unknown Woman, a 1972 work by the Italian painter William Girometti. The blindfolded subject reminds me of my own experiences in Bloomies, endlessly looking for the exit.

The main floor of Bloomingdale’s New York locations offers a dazzling experience for shoppers intoxicated by jewelry, cosmetics, and checkerboard floors. In fact, you could say it’s downright surrealist.

RH and Paul Vredeman de Vries

RH began humbly as Restoration Hardware, a Eureka, Calif., supplier of vintage trimmings that opened in 1979. Since then, its name has shrunk, but its offerings have expanded mightily, and you can find branches in 104 locations in 96 cities, including a 90,000-square-foot flagship in Manhattan. Displaying furniture in commanding venues was part of the grand plan of RH’s CEO, Gary Friedman. The Meatpacking District building’s soaring central atrium with fluted columns is a fitting temple of commerce — or maybe a church? Compare the awe-inducing proportions to those of the Flemish painter Paul Vredeman de Vries’s Interior of a Gothic Cathedral from 1596-1597.

Tuckernuck and Pierre Bonnard

Designed by CeCe Barfield, the Tuckernuck clothing and accessories store on Madison Avenue has a cozy, pastel, and patterned domesticity that is reminiscent of the interiors painted by the French Post-Impressionist artist Pierre Bonnard. A sun-lit bay with mint green walls, tabletop goods, and a rack of printed fabrics projects a strong family resemblance to the breakfast room shown in Bonnard’s Interior with Head, from 1914-1915.

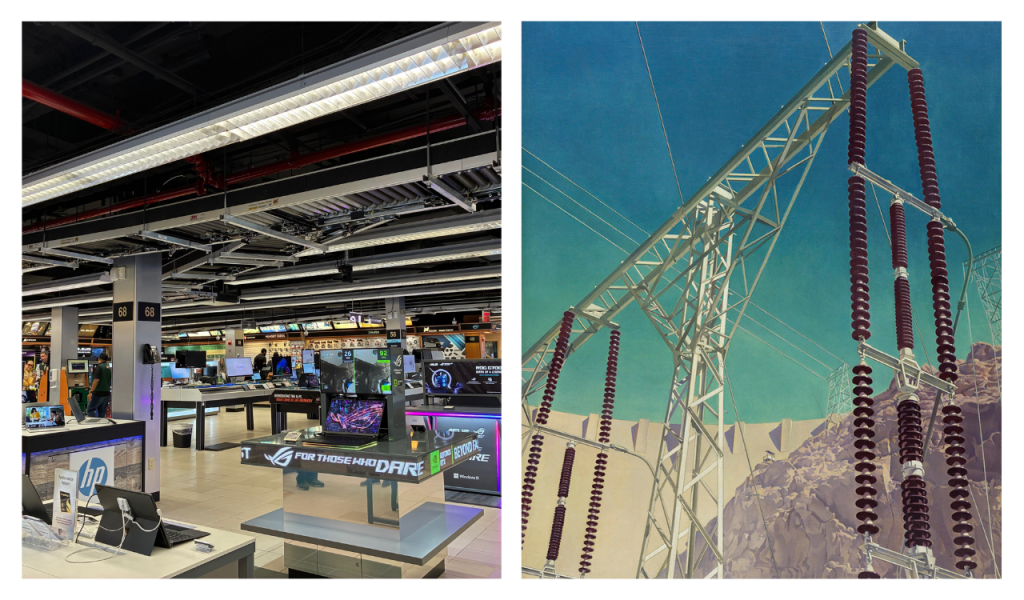

B&H and Charles Sheeler

B&H was founded in 1973 as a photography retailer. It is now a photo, video and audio behemoth on Ninth Avenue, with more than 400,000 products. The interior is 100 percent functional — its most notable feature is a conveyor belt running through all three floors — but that doesn’t prevent it from calling up associations with the paintings of Charles Sheeler, including Sky and Earth (1940). A self-taught commercial photographer before he became a painter, Sheeler documented U.S. industry in the mid-20th century in a style called “Precisionist.” Notice the strong use of parallel lines in both cases.